Hunter is one of the new flagships of the European supercomputer landscape. During a meet and greet with Hunter, we use both our ears and eyes to take it all in.

Walking around a university makes us nostalgically remember our own student days. As inexperienced freshmen, we already mistake the building upon arrival. The displayed race cars catch our attention, but that’s not why we traveled to Stuttgart.

The Höchstleistungsrechenzentrum, which we’ll call HLRS from now on, looks like an ordinary university building from the outside. Little suggests upon arrival that this is Germany’s national supercomputer center. HLRS houses Hunter, which was commissioned earlier this year.

Fast Cars

Before we’re allowed into the data center, after being welcomed with savory and sweet German snacks, we’re first asked to take a seat in an auditorium. Instinctively, we sit in the third row to avoid difficult questions from the professor, though this time it’s the other way around. Michael Resch, who can place the triple title professor-doctor-engineer before his name, introduces Hunter.

Hunter reaches a peak computing speed of 48.1 PFlop/s, which is twice as fast as its predecessor Hawk. “The peak doesn’t really interest me. For me, that’s like throwing a car from an airplane and measuring how fast it falls. Nice to know, but not very useful in practice. We have 800 users who just want the best solution”.

“Benchmarks just sell well”, admits Utz-Uwe Haus, who sits at the table as head of HPE’s HPC research centers. HPE can call itself Hunter’s contractor. “Speed is a driving factor, but not the only one to be competitive. To stay in the car theme: giving everyone the fastest car doesn’t solve traffic problems. You need to invest in a complete ecosystem”.

On Instinct

Hunter is as much a showcase for HPE as it is for AMD. The chip maker is represented by Director Solution Architect Jörg Roskowetz. AMD has dominated the supercomputer top lists for several years now. That’s an important recognition for the company, which must compete against rivals Intel and Nvidia. “Industry leaders use our server chips”, Roskowetz proudly states.

read also

AMD aims to knock AI king Nvidia off its throne

Hunter’s secret weapon lies in the hundreds of Instinct MI300A processors packed into the computer cabinet. “The HPC market is shifting in a new direction, where the heavyweight moves from CPU to GPU. This requires new architectures”, says Resch.

Don’t just call the Instinct MI300A a GPU. AMD prefers the abbreviation APU, fully accelerator processing unit. The chip contains not only GPU cores but also Zen 4 CPU cores known from AMD’s Epyc processors.

Roskowetz: “The advantage is that the CPU and GPU have access to the same memory. This saves many calculations and consequently energy. Per hour, AI data centers consume almost as much energy as all of Germany. Chips are just part of the puzzle. If one component fails, the rest fails too”.

Roskowetz passes the ball back to partner HPE. The HPE Cray EX4000 architecture, designed for supercomputers, combines computing power with storage and network in one package. “There’s a lot of talk today about ‘AI gigafactories‘. In the future, they will be able to contain up to hundreds of thousands of GPUs. That seems like a lot, but the ecosystem is ready.”

Humming Fans

Then it’s finally time to start the tour. Entering a data center comes with the necessary safety protocols. Bastian Köller, who watches over Hunter, asks us not to touch anything. “What you break, you pay. If you’re pregnant or wear a pacemaker, entry is at your own risk”.

Two things immediately stand out when entering the Computer Room. It looks remarkably empty. The Hunter computer is tucked away at the back, on the left we see a workbench, and on the right additional server and storage cabinets. The second thing you can’t miss is the loud and constant hum of the ventilation: as if an airplane is ready for takeoff. We feel sorry for our guide who fights an unfair battle to make his voice heard over the fans.

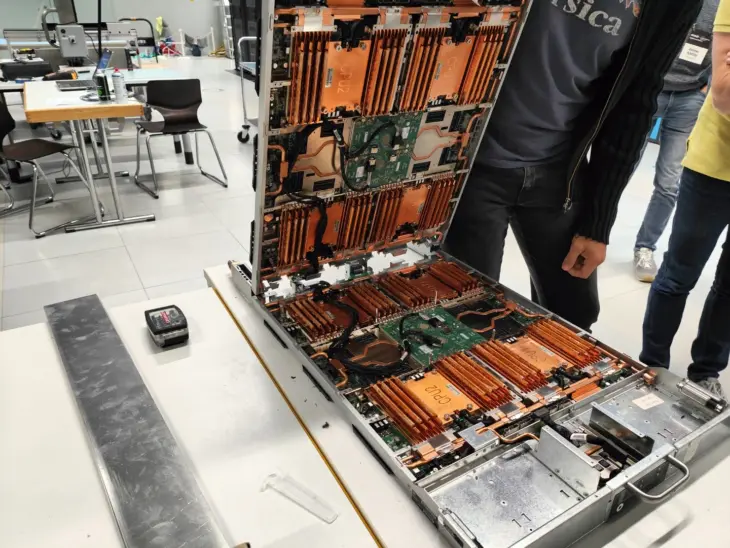

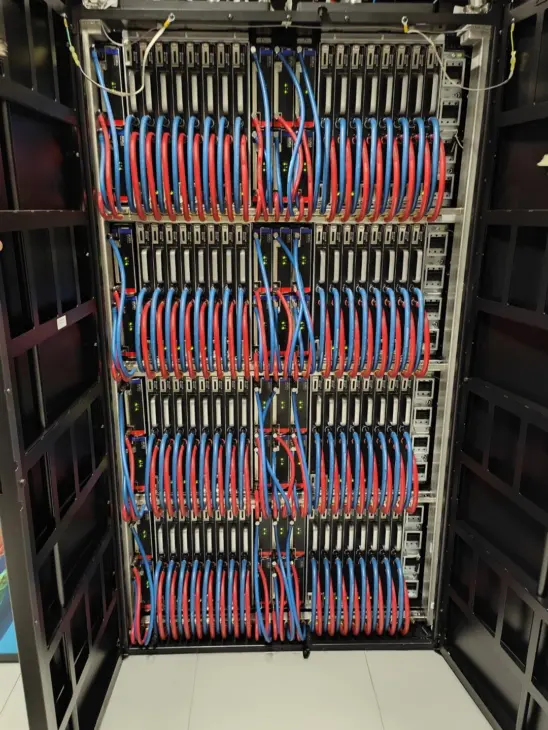

A supercomputer like Hunter looks nothing like a classic PC. The row of cabinets would remind a layperson more of a gym or swimming pool locker room. The guide opens a random cabinet. In each ‘compartment’, the CPUs and APUs run around the clock. The network equipment that connects everything is at the back.

The sound in the room is much more pleasant as we get closer to Hunter. The system uses direct liquid cooling: a technique that runs liquid through servers instead of blowing air. More pleasant for the servers, but especially for the ears.

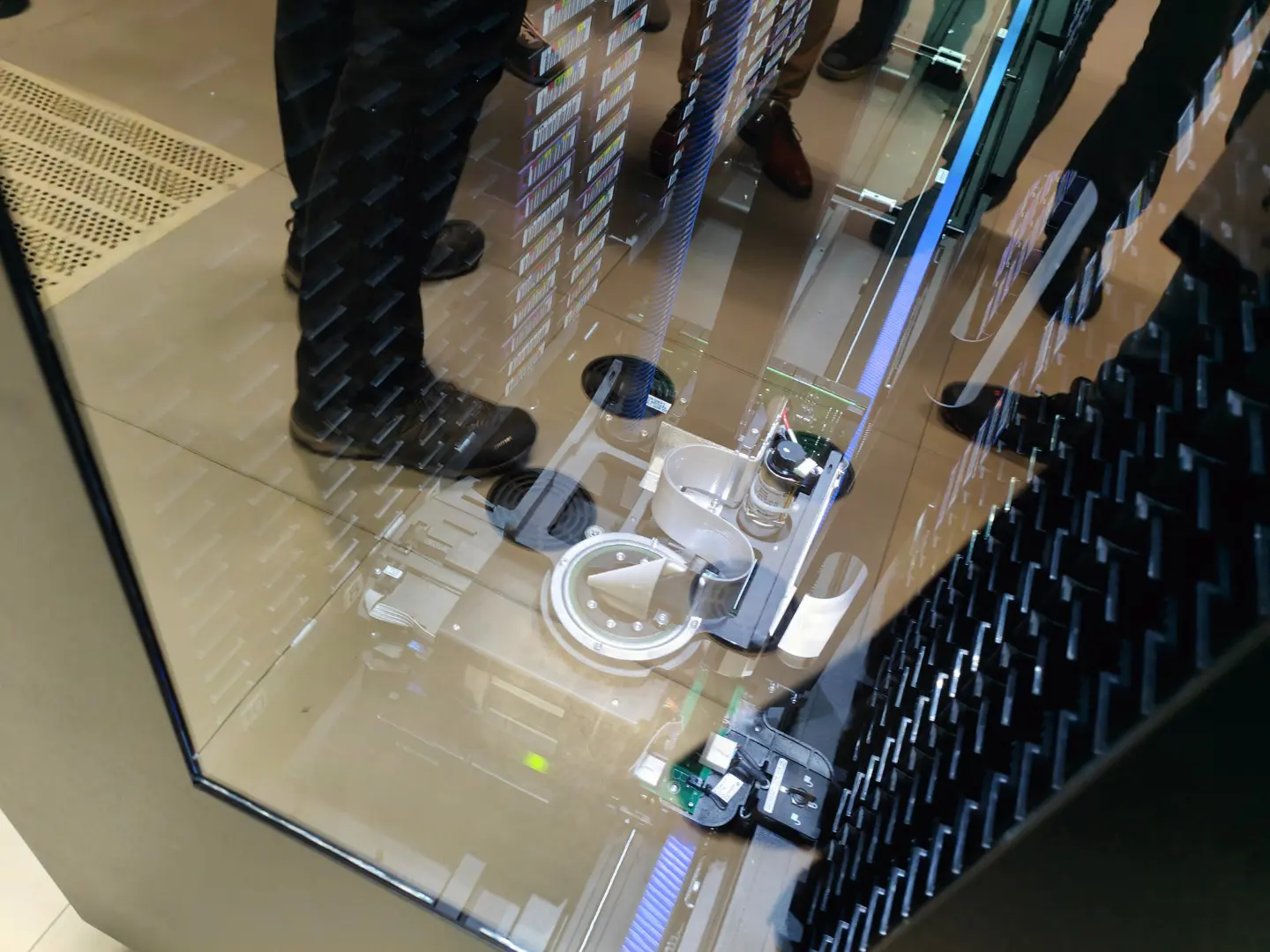

The guide takes us to the storage section. This is where long-term data storage is provided. “Storage on the system itself is only intended for data in active use. For longer storage, tape still offers a safe and efficient alternative, even if it might seem old-fashioned”, says the guide while producing a roll of tape. “On one roll we can store up to about 6 TB for multiple years”.

At the Restaurant

The underlying purpose of the tour is also to show what Hunter is used for. HLRS opens up the system to other organizations that don’t have their own supercomputer. Dennis Dickmann, CTO of AI company Seedbox, and Tom Schneider, Managing Director R for TRUMPF, manufacturer of laser machinery, are invited as customers. “We searched long for the right partner, until we discovered they lived next door”, says Schneider.

That HLRS as a research institute ‘sells’ computing capacity raises critical questions from the press present. Rensch parries: “The price we ask is what it costs us to offer this service, not a euro more. Building your own supercomputer costs millions of euros. When you go out for dinner, you don’t want to buy the whole restaurant either.”

“We offer organizations the flexibility and control to turn our system on or off when they want. But unlike commercial providers, we cannot afford to guarantee continuous availability. The client must accept that”, he continues.

City Trip in 3d

Of course, HLRS is also a daily user of the Hunter computer. To demonstrate this, we are led to the Cave 3D: a true playground for virtual reality enthusiasts. The hum of the computer room can quietly fade away, as now the eyes are put to work. Why there’s a drum set in the room remains a mystery.

We put on 3D glasses and suddenly see a virtual copy of Stuttgart. The simulation flies over famous landmarks like the Fernsehturm and the Schlossplatz. There is indeed a social benefit behind it. “We make the models available for urban planning and research into the impact of climate change on spatial planning, among other things”, says an employee who eagerly waves his virtual pointer.

“The digital twins are developed by combining images made with drones, just like Google Earth. Sometimes we also rely on an external partner for the images”. Then it’s time to “land”.

“This image looks messy now, but with manual modeling we can add more detail”. A press of the virtual button and suddenly it feels like we’re walking in the streets of Stuttgart. “The more detail, the more computing power is required”, the employee reminds us why a supercomputer is running one floor up.

After this first demo our eyes are already feeling heavy, but it’s not over yet. From Stuttgart we move to the wine region along the Neckar River and the Black Forest, while a colleague takes over the virtual baton. “By simulating weather conditions, we can predict whether it will be a good wine harvest”. Sometimes a digital twin serves to make peace. “A new water turbine in the Black Forest sparked a lot of protest. This way, the impact was made tangible for the public and experts”.

European, but not Sovereign

HLRS is preparing for the future. The construction site we see as we enter the parking lot at

will one day become a brand new data center. Hunter will not be moving with it. Not only because moving a supercomputer is not obvious, but also because the university wants to have a successor ready by the

next decade. ‘Herder’ should break the symbolic exascale boundary.

HPE will handle the construction again, but Resch won’t reveal who will supply the chips. “Negotiations are ongoing. We might not have the knowledge about how to build such a system, but we know very well what we want, today and five years from now. Ordering supercomputers is an art. To find the right partner, you need to know what’s possible, but especially what’s impossible.”

With Hunter and soon Herder, HLRS plays an important strategic role for the European Union. Resch is skeptical about sovereignty. “Politicians wave millions around to develop their own chips and supercomputers, but actually delivering that money is often a different story. If the best solution comes from Europe, we’ll take it, but the EU can’t force us to do so”.

read also

EU Sells Hot Air with Digital Sovereignty Strategy

“Sovereignty doesn’t mean you have to do everything yourself. Do you know one country that is completely sovereign? The best example I can think of is China, and their chips haven’t blown us away yet. The term historically emerged from debate around nuclear weapons. We are researchers and refuse to compromise the quality of research for political interests”.