What if telecom providers were to gain access to the entire upper 6 GHz frequency band? In Machelen near Brussels in Belgium, Orange and Nokia are demonstrating how this frequency is suitable for a very consistent and fast connection. The question now is whether Europe will reserve the spectrum for mobile providers, or heed the demands of the Wi-Fi lobby.

On the cycling bridge over the A201 in Machelen, on the border with Brussels, a demo device achieved a download speed of 2.4 Gbit per second. A week earlier, the demo achieved a peak download speed of 3.2 Gbit. The device is connected to a special 5G transmission mast atop the abandoned Capgemini office. This mast features an additional antenna that transmits in the 6 GHz spectrum. The test is a first for Belgium.

The highway is getting congested

Today, your provider broadcasts its 5G network over a segment of the 3.5 GHz frequency band. During the frequency auction, each provider was allocated approximately 100 MHz of spectrum (in Belgium). This spectrum can be envisioned as a highway with a hundred lanes. All traffic between devices and masts within a 5G network occurs on this highway.

A hundred lanes is substantial, but insufficient. Nokia, Orange, and other telecom players concur on this. A Nokia study suggests that network traffic will increase by approximately 2.5 times between today and 2030. By 2030, or potentially even sooner, there is a risk that the 100 MHz highway on the 3.5 GHz frequency band will become congested.

Limited free space

The solution: a new, significantly wider highway of 200 lanes per provider on the 6 GHz frequency band. In the EU, most of the available radio spectrum has already been allocated. Not only providers, but also other entities including NATO, hold a share of the pie. Only in the so-called Upper 6 GHz band (6.425 – 7.125 MHz) is there still free space.

read also

5g over 6 GHz: Faster than expected, and essential for the future according to Nokia and Orange

European telecom providers assumed that the European authorities would prepare the band for allocation. The CEPT (Communications Networks Content & Technology Directorate-General) was mandated to do so. And then the Wi-Fi 6E standard emerged.

Other interested parties

Wi-Fi 6E is a variant of Wi-Fi 6 for wireless internet at home. Wi-Fi typically uses frequencies on the congested 2.4 GHz band, which also hosts Bluetooth, and since Wi-Fi 5, also the 5 GHz band. Wi-Fi 6E adds compatibility with the 6 GHz band.

The Dynamic Spectrum Alliance (DSA) argues that the future of Wi-Fi is at stake. According to the DSA, 6 GHz is crucial for its further development. In an open letter to the European ministers responsible for digitisation, the industry association states that it would be a mistake to reserve the spectrum for a 6G rollout that may never happen. They argue that it is necessary to keep the Upper 6 GHz band free of licences and thus de facto reserve it for applications such as Wi-Fi.

More lanes, same investment

Providers are not in favor of this. They want the entire Upper 6 GHz band to be allocated for mobile networks. This would allow providers in Belgium to acquire 150 MHz to 200 MHz. If the Wi-Fi team prevails, it will likely be closer to 100 MHz per provider. The DSA’s 6G argument is proactively refuted during the demonstration in Machelen, where the 6 GHz band is utilised with 5G technology.

However, the investments required to deploy 6 GHz are not significantly greater for 100 MHz than for 200 MHz of spectrum. If Wi-Fi 6E receives a portion of the 6 GHz spectrum, then Orange, as well as Telenet, Proximus, and potentially Digi, face a halving of the return on a potential investment.

6 GHz: challenges and solutions

It’s not by chance the demo in Machelen is taking place now. Next week, regulatory bodies in the member states must take a position on the use of 6 GHz. They do so as stakeholders within the European Radio Spectrum Policy Group (RSPG), which will determine its official position on the use of 6 GHz this month and will strongly influence the work of the CEPT. On the outskirts of Brussels, Orange and Nokia now aim to prove that 6 GHz is exceptionally suitable for broadcasting a mobile network.

This is not self-evident: the higher the frequency of a signal, the smaller its range. In theory, at least. The problem, however, comes with its own solution. If the frequency doubles, not only does the packet loss on a signal double, but the size of the antennas also approximately halves.

MU-MIMO and beamforming

This means that a 6 GHz 5G antenna on a pole contains many more individual antenna elements internally: from 192 for classic 3.5 GHz 5G to as many as 700 for the 6 GHz demo antenna, with the possibility to link even more.

These antennas can be individually directed, sending a concentrated signal in a specific direction. This is called beamforming. Such a directed signal reaches further than a broadly broadcast alternative. The more small sub-antennas there are, the more focused the signals can be.

Through MU-MIMO technology, also found in 5G and Wi-Fi, a device such as a mobile phone can consistently connect to a directed signal. In theory, this should compensate for the signal loss of 6 GHz.

More than compensated

What is evident in Machelen: ‘compensating’ is an understatement. The demo antenna consistently delivers higher 5G speeds than the classic 5G signal on 3.5 GHz.

We walk around office buildings in Machelen, monitoring the throughput speed on a mobile device. The transmission mast for the test is approximately 300 meters away. With a direct line of sight to the antenna, the download speed comfortably sits around 1.5 Gbit. If we move behind the office buildings, the signal remains above 1 Gbit.

The additional beamforming enabled by 6 GHz amply compensates for the inherently lower range of a 6 GHz signal. In this scenario, 6 GHz consistently proves to be the superior carrier compared to 5G. Furthermore, the prototype 6 GHz antenna transmits with merely 30 watts, while the 3.5 GHz antenna uses 100 watts.

We observe speeds that are one and a half to three times higher on 6 GHz than on 3.5 GHz. Indoors, the difference is smaller, but 6 GHz still performs slightly better than 3.5 GHz. The speeds between the buildings even surprised the experts from Nokia and Orange. They had anticipated a greater drop in connection speed, but MU-MIMO technology performs exceptionally well in real-world scenarios.

Proof provided

With this demo, Nokia and Orange aim to prove that 6 GHz is indeed exceptionally suitable for 5G and future networks. The test was conducted using a Nokia antenna on Orange’s standalone 5G network, without extensive optimizations for 6 GHz.

With this demo, Nokia and Orange aim to prove that 6 GHz is indeed exceptionally suitable for 5G and future networks.

A small degree of nuance is appropriate: nobody else is currently transmitting on 6 GHz, and Orange also used just one antenna. Interference is therefore minimal. In real-world daily use, antennas do interfere with each other, although in theory, that interference on 6 GHz should also be smaller than today with 3.5 GHz.

Future-proof without additional masts

The results imply something else: since 5G over 6 GHz provides a better signal via beamforming than 3.5 GHz, the coverage of existing radio sites is sufficient. Deploying 6 GHz does not require additional transmission masts beyond the existing infrastructure.

With this demo, Orange and Nokia present a strong argument against the Wi-Fi lobby, although the latter can contend that a division is indeed an option. Today, providers have 100 MHz on 3.5 GHz, so why would an additional 100 MHz on 6 GHz not suffice, and why do they absolutely need 200 MHz?

The providers refer to their own studies on mobile network usage, which is growing exponentially. They argue that 100 MHz would quickly prove insufficient.

What about other frequencies?

In the US, Wi-Fi does receive the 6 GHz band, but the situation there is different. More spectrum is available overall. The pie is larger there, so everyone can get their fill.

And what about other frequencies? 6 GHz is the only free spectrum around these relatively low frequencies, but for example, there is also space at 26 GHz. However, that doesn’t make a significant difference.

A 26 GHz signal attenuates much faster than 6 GHz. The MU-MIMO technique with extra antennas and beamforming is not infinitely scalable. In these very high frequency bands, the model with current radio sites is no longer sustainable, and the country would need to be dotted with additional antennas. In practice, this is not feasible, it is stated, except in niche locations such as specific squares or festivals. 26 GHz certainly does not offer the same structural solution as 6 GHz.

Europe decides

The CEPT will finalize its first draft report for the European Commission in March 2026. In it, they must weigh the demands and arguments of the providers against those of the Wi-Fi team. The final report will follow in the summer of 2027, after which the Commission will presumably finalize the regulatory framework sometime in 2028.

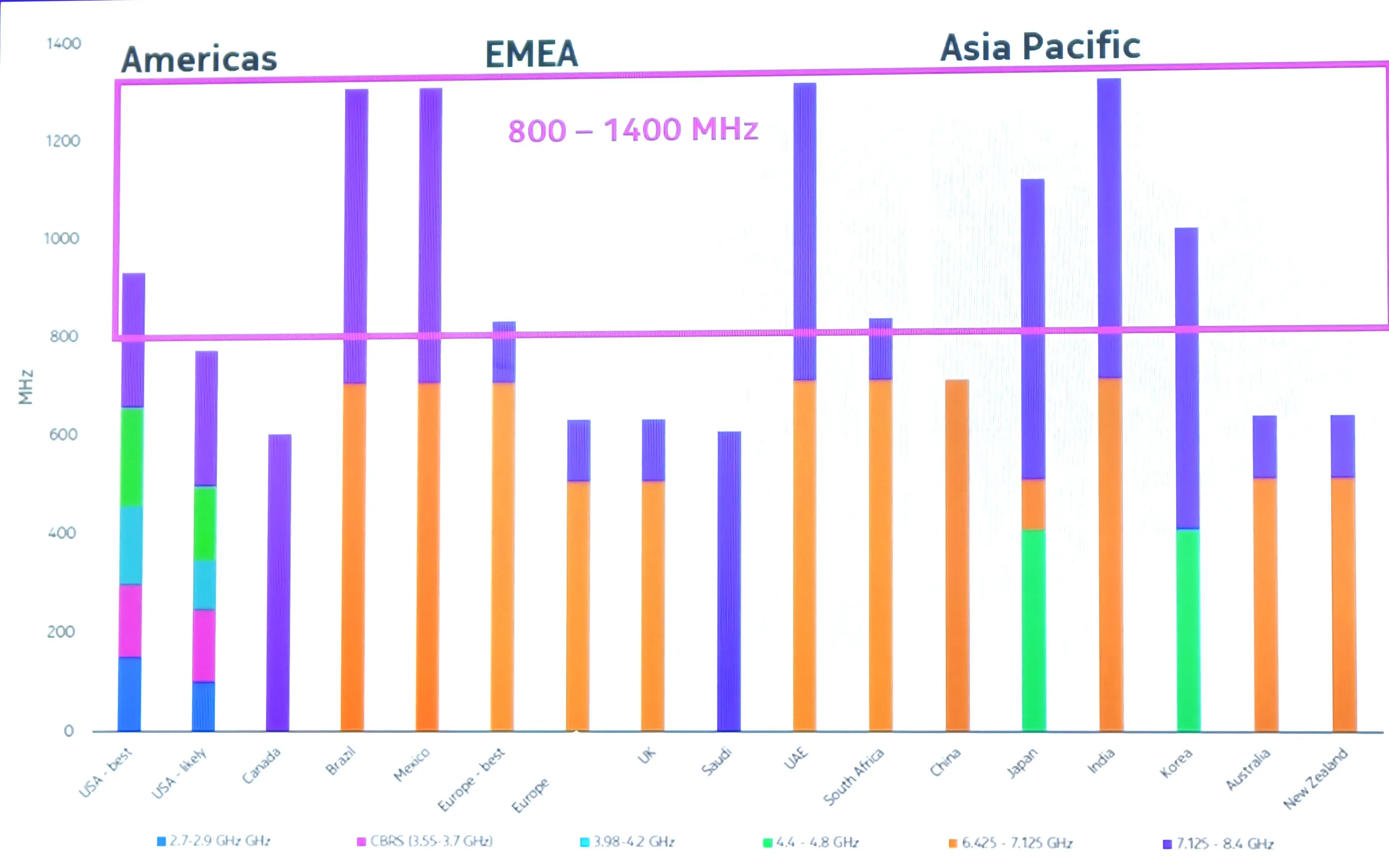

If Europe decides to allocate too much of the spectrum to Wi-Fi, operators fear a difficult-to-compensate disadvantage compared to the rest of the world.

During the demo, Orange speaks for the entire telecom sector and hopes that the Upper 6 GHz band will be allocated exclusively to telecom providers. In Europe, much less spectrum is available than in the US or Asia. 6 GHz is the last freely available, exceptionally suitable frequency currently under consideration. If Europe decides to allocate too much of the spectrum to Wi-Fi, they fear a difficult-to-compensate disadvantage compared to the rest of the world.

The router manufacturers also have their arguments. 6 GHz indoors enables higher speeds and the frequency is also relatively free from interference. This would boost the performance of wireless connections and enable more high-quality simultaneous connections. The Wi-Fi Alliance and the Dynamic Spectrum Alliance fear that Europe will fall behind if the spectrum is allocated exclusively to the telecoms sector.

How these interests are weighed against each other will determine what tomorrow’s mobile networks will look like, how much spectrum providers have available to serve customers, and how many lanes they receive for their investment.